Welcome to all of the new subscribers! Thanks for being here. I’d enjoy hearing from you in the comments, and if you have a Substack send me a link to your writing. This is part two of “Talk therapy will save your soul,” a five-part love story with (and redefinition of) talk therapy. You can read part one here.

IN THE LAST ESSAY I questioned the proposition in many corners of psychotherapy that words are crummy for healing. And that something like the opposite might be true: We’re buffering ourselves from real conversation in talk therapy with methods and techniques to keep each other at a safe distance—to stay alienated. Why would we do that? It’s not because there’s a Cabal of Therapy Elders conspiring to keep us struggling with our “mental health,” but more like a civilizational tilt (to borrow a phrase from Charles Eisenstein) away from authentic human connection and the freedom and aliveness that comes with it.

In my experience, the return from alienation leads right through immense pain and grief on our way back home. Few are willing to walk this road with us. It’s a situation that each of us has the opportunity to look at directly in our lives—or not. Either way is a choice.

“All actual life is encounter”

Now would be a good time to get specific on what I mean by “talk therapy.” I’m describing a spontaneous, non-goal directed conversation between therapist and client, in which the therapist offers a heightened kind of attention. The therapist “attends,” in the spirit of the original meaning of the word therapy (therapeúō) in Ancient Greek. The ground of talk therapy or the basic intention is the human-to-human encounter, what Rollo May called “a total relationship going on between two people.” Before him the existential philosopher Martin Buber called it the I-You (or I-Thou) relationship.

This is direct and unmediated, real, a holy kind of relationship where I don’t put labels on you and think I know who you are because of your symptoms. I don’t think I know how to fix you. I approach you with wonder. You are mysterious. I do not “know” you or even really think I’ll ever understand you. I encounter you and attend to you. You reveal yourself to me.

“All actual life is encounter,” Buber writes.

The alternative to actual life is the barren land of mediocrity Buber calls the I-It world. It’s functional, linear, causal. The everyday chop of going through life, using the world and collecting experiences. Buber gives the example of all the ways we might experience a tree: its structure, how it stands in the ground, its movement, assigning it a species, even understanding it as pure math. Sounds a lot like normal life in the fading age of scientific materialism—but this is all I-It. It’s a necessary condition of life for selecting a cabbage at the grocery store driving it home safely to the humidity-controlled fridge drawer. But getting lost in the world of relating to trees and people as objects feels like you’re starving all the time even though you’ve eaten, like you have everything you could possibly need but wake up in the morning feeling impoverished and anxious.

Then there is the possibility of being drawn into a real relationship with the tree—into life!—which happens through a combination of “will and grace.” Everything else about the tree is included in this relationship, except now something is different. We’re called to deal with each other in a new way, confronted with each other’s bodies and being. We’re in reciprocity. What’s happening here is not fully describable. The I-Thou encounter is timeless, boundless, ineffable.

Truth does not ‘inhabit’ only ‘the inner man’, or more accurately, there is no inner man, man is in the world, and only in the world does he know himself. - Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception

Objects and persons in psychotherapy

The Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing was following a similar thread in therapy. He said there are basically two types of therapy. In one, the client is an object-to-be-changed. In the other, the client is a person-to-be-accepted. Any way of doing therapy in the first category “perpetuates the disease it purports to cure.” That’s a radical claim. He’s saying that there’s something about treating each other as objects—using, coercing, not really taking each other to be legitimate human beings with our own mysterious unfolding—that actually keeps us grinding away with our psychological distress.

That kind of treatment is part of what got us twisted up so badly in the first place.

It’s what led us to retreat from encountering life.

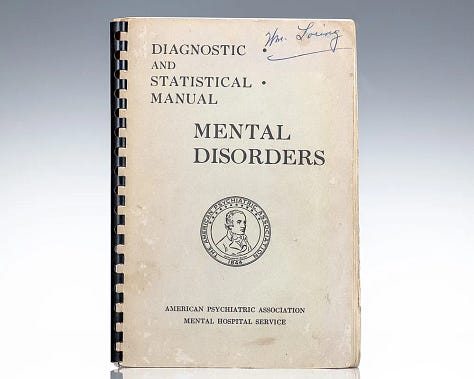

To grok the art of object-to-be-changed healing, look to the dominant medical paradigm of therapy. It proceeds from assessment, to diagnosis, to treatment plan using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. I meet you, and instead of encountering you, I abstract your experience as symptoms that match up with one or more of nearly 300 mental disorders, and we get you into some kind of evidence-based program to shift you some number of points on an abstract scale meant to approximate good “mental health,” a term that is everywhere ill-defined.

I dial your knob down a few clicks on the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), dial your knob up a few clicks on the Mental Health Quality of Life questionnaire (MHQoL). Off you go buddy.

It’s got I-It scrawled all over it.

We never really have to deal with each other human-to-human because we’re meeting through a filter, an interface, paperwork. What’s at stake here is everything: As a client, we miss out on the opportunity to be met as a legitimate being perhaps for the first time without imposition. This restoration of legitimacy, of our beingness, is at the core of what I take to be healing. The change is ontological, to use a word that took me the last six years to understand. The soul gasps for that long-awaited sip of air and says yes I may make a home here after all. Grace. Encounter. Psychotherapy: to attend to the soul.

It’s not inner work. As the existential-phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty said, “there is no inner man, man is in the world, and only in the world does he know himself.” This is the work between us.

Sneakily, the ways we shuffle around and control each other are also there in the diagnosis and treatment of trauma that has engulfed the therapy industry. I say sneakily because it seems so compassionate to want to heal each other’s trauma. But trauma therapy is a hammer searching for nails. We’re right there in the same game of fixing each other with this or that program. (And that may not even be the point. Here’s a controversial take about whether we can even heal from trauma by my mentor Bruce, based on a conversation with his mentor Andrew Feldmar, who also studied with Laing. TLDR: No.) It’s even there in psychedelic science that sees psychedelics as a medicine to heal trauma. Right there in somatic therapy where trauma is in your body and we need to excise it either in a mechanistic way, i.e., by rewiring your nervous system, or through psychospiritual surgery.

As the existential psychoanalyst and philosopher Michael Guy Thompson, who also studied with Laing, says, this is more of a sensibility about therapy than a theoretical or technical orientation. Can you feel it? A sensibility, a way of relating to each other.

Conversation, innovation, magic

I’m calling the other way “talk therapy” for a few reasons.

One is because Freud’s “talking cure” was a real innovation. He normalized neuroses as part of the ordinary spectrum of human experience, rather than pathologizing them. He introduced listening, sharing truthfully, and being in an authentic relationship as the way to a difficult yet liberating journey of being more fully human. He turned us on to the way we see others as projections of the past, as objects, and how to work through this confusion in psychoanalysis for greater freedom. He called this transference—a fundamental rule of psychoanalysis along with the unconscious.

“To what extent may not the subject's instincts, tastes, and psychical faculties be modified by a prolonged and cleverly managed suggestion, whether in the waking or in the hypnotic condition?” - Hippolyte Bernheim, Suggestive Therapeutics: A Treatise on the Nature and Uses of Hypnotism

This was a controversial move at a time when hypnosis was the method du jour for what we today call “mental health disorders.” Hypnosis, which Freud practiced before creating psychoanalysis, involves putting people into a sleep or suggestive form of consciousness to modify their instincts, tastes, and psychical faculties “by a prolonged and cleverly managed suggestion.” Coercion, in other words. Many forms of psychotherapy today carry on in this tradition of hypnosis or other control-oriented healing modalities from the past. Laing pointed to behavior therapy as an extreme example of treating people as objects rather than persons. This is “a technique of non-meeting, of manipulation and control,” Laing wrote. Behavioral therapies, including cognitive behavioral therapies, are the most commonly used today.

So Freud’s talk therapy—it was a new down-to-the-studs kind of healing. An into-the-depths kind of healing. He compared it to excavating a buried city. It’s rugged as hell, and the therapist needs to do it, too. Freud was clear about that. Laing took this therapeutic journey down even further, down to the bones, blood, and dirt. He took it into the most challenging place of all: the relationships between us.

“Psychotherapy consists in the paring away of all that stands between us,” he writes. “The props, the masks, the roles, the lies, the defenses, anxieties, projections and introjections, in short all the carryovers from the past, transference, countertransference, that we use by habit and collusion, wittingly and unwittingly, as our currency for relationships.”

Picture a paring knife: the smallest blade in the chef’s knife roll.

Sharp, fits in the palm, for fine details. I think of a paring knife not for hacking away but for the close-in work of revealing the beauty of what’s already there. Peeling the skin of an apple, segmenting an orange, cross-hatching on a sourdough, removing the pit of a date, releasing the golden edges of a cake from its pan. We remember as we do the delicate work of revealing more and more beauty, that we are in a relationship with the original ingredient. It was only just recently alive and now will give us pleasure and nourishment.

Words function like a paring knife.

Words are invisible messengers that pass between two porous and non-separate, yet distinct, bodies. Words are magic. Words are psychoactive, to borrow a phrase from Bruce. Through some miracle of evolution, some mastery of God’s creation, I can have an experience that takes shape in my psyche and emerges as sound from my body and passes through space and lands in your body, where it might offer you ease, bring you to tears, or incite you to rage. The magic. The jaw-dropping magic of it.

When words come from a place of truth, the therapist’s words can help the client reconstruct reality and cut away the web of confusion that often got stitched up from coercive and false relationships. We were not born to hate ourselves and keep our gifts from the world; we learned it, we continue to pass it on unless we don’t. And that happens right there in the encounter. I cut the elastic band securing my mask. You might remove yours. We may just meet human-to-human.

We’re not removing our bodies from the equation here. We’re seating our words in the body and giving them their right due. We may not even use words. We may sit in silence. Yet the reality is we were shaped by words, conditioned by words, punished by words, driven into exile by words, rejected by words, confused by words, perhaps here and there praised by words. Our antipathy towards words makes sense. But I can’t really renounce words unless I want to go live in a cave—and even then I’ll be muttering to myself until I reach enlightenment, and even then I’m bound to come out and tell everyone about it!

If that sounds like some highfalutin talk therapy, let me say two things about that. First, psychotherapy is big work. To attend to the soul! That’s a profession that really rips. What we call “mental health counseling” is a watered down substitute for the real thing, more like pain management for the soul. I’m not saying there’s no place for it, for tools and techniques, but is that what we really want? Is that what you really want? To shift your score on Beck’s Depression Inventory?

Or in the words of Friedrich Nietzsche, to “clench your teeth, open your eyes, and grab hold of the helm!”

This kind of encounter I’m describing in talk therapy asks much of the therapist and client—a commitment to meeting each other for real—but not in the ways you might expect. Most therapy has either a secret or explicit agenda to “go deep” or get into “what’s important.” When I do talk therapy there’s plenty of bullshitting, talking about ideas and theories, what looks like a regular old conversation. There is no arc to the session or soft landing with key takeaways for my week. These are impositions that some kind of narrative arc is preferable, that he knows it and I don’t. It’s turtles all the way down. There are so many rules and orientations educated into therapists and perpetuated in trainings that say therapy is about a particular kind of outcome achieved through a particular route.

Psychology has also collected all kinds of methods and techniques under the banner of talk therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy, stress coping and problem solving, teaching social and communication skills, mindfulness and relaxation techniques, exposure therapy, Internal Family Systems—all of this is considered talk therapy. None of this is talk therapy.

These are methods. Practices. Frameworks. Schemas and technologies. Parlour games.

In talk therapy the ground is the encounter, the relationship, the conversation. This doesn’t mean there is no technique or theory, or that the therapist doesn’t assume a higher degree of responsibility for the situation, but all of this serves the meeting of two humans in a real way.

And here I stand before you with a paradox. I’ve no doubt that becoming more mindful or feeling a shimmering spectrum of emotions and sensations is an advantage to living a meaningful life. Recall from the last essay: I’m tracking the emotional content in my left groin. However, any kind of ambition about it may be any one of several obstacles to human-to-human connection Laing is talking about. The most likely outcome is that the client begins to perform for the therapist a certain thing that looks like healing—and maybe it is! Or maybe it’s just another mask to take off several years down the road with another therapist. In performance I walk around at best as a silhouette of myself.

(The psychotherapist Tara Rae Behr has explored the phenomenon of performance in therapy, especially with psychedelics, at length. I recommend reading her piece on Mad in America, “The power dynamics of psychedelic therapy” and popping over to her Substack.)

Talk therapy is about removing barriers to really meeting—to love—which, to be clear, is what this is about. Love: that exiled word in psychotherapy. Mostly this happens through talking, a way we’ve conveniently been getting to know each other for at least a few hundred thousand years.

How did we lose faith in our words and get disconnected from our experience? That’s the subject of part three, which is coming soon.

I’m curious what you think: Do therapy techniques and methods “perpetuate the disease they purport to cure”?

Read part one here:

Talk therapy will save your soul

“Talk therapy will save your soul” is a five-part romance with (and investigation of) talk therapy. We’ll cover existential philosophy, encounter, the crisis of experience, the uprooting of language, what healing is, and more. It’s the first series of essays on

Beautiful essay. It's rare to find words that carry such heart and truth these days. I have more to reflect in coming days. Thank you for sharing your words with the world, Jeremy.

Your essay is an act of devotion. It gestures toward a more humane, daring, and dignified form of therapy, rooted not in procedure, but in presence; not in optimization, but in love. You describe the possibility of being met in our full humanity, without scripts, scales, or fixes. That kind of encounter, you rightly suggest, may be the closest many of us ever come to grace.

And yet I find myself wondering—not whether you’re wrong, but whether the vision you’re defending can bear the weight of the world we live in.

You are not mistaken that something has gone wrong. Our society is suffering not just from chemical imbalances or trauma histories, but from a more profound estrangement—from each other, from language, from shared meaning. The bureaucratization of care, the psychologizing of suffering, and the thinning of friendship and ritual all contribute to a quiet despair that many experience not as a crisis but as the default condition of their lives. In this context, your call for a real conversation that is undefended, unplanned, and unmechanized is not just noble. It is necessary.

But necessary is not the same as sufficient.

For many people, especially those living with conditions like OCD, PTSD, or major depression, the tools you critique—diagnoses, protocols, structured methods—have been life-saving. They are not substitutes for relationships but often prerequisites to them. A person drowning does not first need to be understood; they need something that floats. You gesture toward the soul; others simply need to survive the morning.

To reject these methods wholesale, even in the name of love, risks replacing one form of abstraction with another. We must be careful not to romanticize intimacy in a way that obscures the ordinary labor of healing. Even the most skilled therapist cannot offer unconditional presence to every client, nor should they. There is no intimacy without limits, no trust without structure, and no depth without preparation. What you call encounter, others may experience as ambiguity, even exposure. In some cases, the effort to “be real” can become its own subtle form of coercion.

And then there is the moral question: what kind of culture are we forming through our practices of care? A society cannot be built solely on unmediated encounters. We also need norms, institutions, and shared moral language. We need durable commitments that survive our moods and hold us accountable to one another. Without these, even our most sincere efforts at healing risk collapsing into an expressive individualism that may be a beautiful solitude, but is solitude nonetheless.

Finally, I worry that your vision of therapy, though sincere, may at times ask too much of both therapist and client. Not everyone comes to therapy seeking transformation. Some come to repair, to stabilize, to endure. And that is not a failure but a form of wisdom. There is quiet heroism in simply continuing.

But I do not write this to diminish your vision. I write because I share your longing for deeper conversation, for moral seriousness, and for human dignity that isn’t flattened into a treatment goal. What you describe is not merely a method but a kind of faith. And perhaps what we need most now are people willing to defend such faith, even as they come to terms with its limits.

So yes, keep pressing us toward something more tender, more courageous, more honest. But remember, too, that not all silence is evasion. Not all methods are masks. And not all healing looks like revelation. Sometimes it looks like someone quietly choosing to live.

Joshua