Meet the first man to get stuck in his head

Part 3 of “Talk therapy will save your soul” takes a trip 2,500 years into the past for a few jugs of wine and the origins of rational thinking.

IN THE LAST TWO ESSAYS (one and two), I made the case that we’ve been misled into thinking that words “don’t go deep enough” for real healing in therapy. This seemingly innocent claim made by body-focused (or “somatic”) therapists takes us down a rabbit hole of curiosities. What exactly is deep down there in need of healing? What’s really happening in psychotherapy? Why have our words lost their magic—and, more generally, why are we so disconnected from our experience?

I want to dig around that last question now, by visiting a very important moment in history when we split off from our experience and lost our voice: the beginning of rational thinking. My hope is that by tending to the roots of the Western mind, we can find our way again to words that make the full journey through our hearts and into the Earth.

I. “You don’t know sh*t plebe” - Parmenides

Pack your wool satchel carry-on and a jug of wine. You and I are traveling 2,500 years into the past, sometime between 475 and 450 BC, to Ancient Greece, in a colony called Elea on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. This is south of Naples in present-day Italy, right around the laces of the boot if you’re looking at a map. The water sparkles and laps against sandy beaches and rocky, mossy coastal foothills. Golden eagles soar in the pristine sky. Whales and dolphins breach the surface on the horizon. The smell of oregano and other wild herbs wafts in from the Mediterranean scrub on the warm breeze, catching your nose hairs with salt and moisture.

You and I are sitting in the agora, or town square, near Elea’s acropolis munching some olives and drinking wine. It’s more like a working vacation than a holiday. I just finished my work day apprenticing at the potter’s wheel and you’re tan from catching fish all morning. Other townspeople begin to gather as golden-hued light massages the visible world into soft focus. Heat escapes the air, following the sun toward the horizon. Now some eighty of us are sitting on stone benches and coarse linen blankets on the packed earth. Torches flicker at the edges of the square. I snatch a hearty loaf of bread from a vendor and refill our wine jug.

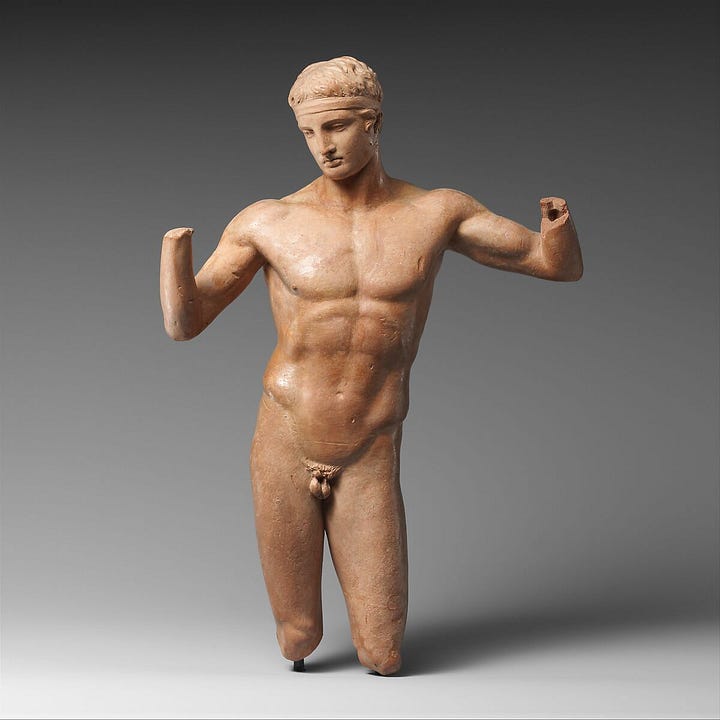

The buzzy energy of the crowd comes into alignment as a man appears on the street just east of the agora flanked by three assistants who seem to flit about him like mosquitos, excited and self-indulgent. His linen tunic flaps gently in the breeze. I look down at mine, stained from wine and clay, too tight at the waist. I pull at it and try to sit more upright, reminding myself that tomorrow morning I’ll do some calisthenics, maybe wrestle my neighbor Androcles. It’s time for a new tunic but the price of barley meal is just so high these days. What am I, made of coins? You nudge me.

“Hey, pay attention,” you say, pointing east. “Parmenides is here. That’s Zeno holding his jug of wine.”

Parmenides is the head of the Eleatic School of philosophy. I imagine him as an Ancient Greek Jordan Peterson, but a much bigger deal, an intellectual heavy hitter on the level of Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Pythagoras. Not the kind of guy who would make an appearance on Sam Harris’s podcast. He recently got back from a speaking tour in Athens where he met a promising young man named Socrates. Graying chestnut curls of hair frame his forehead. The sun casts a warm glow on the temple of Athena behind us. Parmenides wipes sweat from his brow, clears his throat, takes a swig of wine, pumps his fist three times toward the crowd, and begins to recite a poem that will change the world forever.

In On Nature, he shares his encounter with a Goddess who tells him the nature of knowledge and the world. He begins with the incredible journey to meet her:

The car that bears me carried me as far as ever my heart desired, when it had brought me and set me on the renowned way of the goddess, which leads the man who knows through all the towns. On that way was I borne along; for on it did the wise steeds carry me, drawing my car, and maidens showed the way. And the axle, glowing in the socket—for it was urged round by the whirling wheels at each end—gave forth a sound as of a pipe, when the daughters of the Sun, hasting to convey me into the light, threw back their veils from off their faces and left the abode of Night.

Maidens, an axle glowing in its socket, the sound of a pipe! Sounds a lot like a psychedelic trip. And who knows? Maybe the old Greek got high and wrote a poem. There are some scholars who believe he was engaged in initiation rites in underground caves. Whatever the origins of his ideas, they had an unusual impact on history: While we often think of consciousness expansion as an opening of our minds, this encounter with the Goddess may have closed the minds and bodies of the West for millenia—to this very day.

The Goddess instructs Parmenides in an early form of logical argument to explain the nature of reality. The philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend explains what Parmenides was up to in the book Conquest of Abundance, which is about the rise of abstract and scientific thinking. He says that “the key assertions of the story are to be established neither by habit derived from experience (ethos poly’peiron) nor by the aimless eye or the echoing ear, nor even by mere talk (my emphasis); they will be established by proof (logos).”

Forget your experience. Forget your senses. Forget the way you typically use words. Proof baby.

The argument goes like this: Everything consists of Being, which is everything, and not-Being, which doesn’t exist. The cash value of this argument is that everything is only ever Being, with the radical implication that when people experience change and difference in the world, it is only an illusion. Everyday reality is not what it seems. Ultimate truth is veiled, out of view, accessible only through this special type of thinking and reasoning. He believes this to be objectively true, a radical departure from a world that was, until then, mostly dynamic and relational.

“This is what I bid thee ponder,” Parmenides says, pointing a big oily finger right toward you and me.

“I hold thee back from this first way of inquiry, and from this other also, upon which mortals knowing naught wander two-faced; for helplessness guides the wandering thought in their breasts, so that they are borne along stupefied like men deaf and blind.”

You’re looking at him with your head cocked sideways. He just said you’re helpless and stupefied. How are you feeling about that? Take a minute to check in. I take a big bite of bread, chewing numbly, not sure if I’m stupefied by the wine or because of what I’m hearing. I feel confused, dizzy, anxious. Do I not really make jugs for wine, oil, and grains? Is my kiln fire an illusion? Someone behind us whispers “asshole” under his breath. A guy in the back yells, “If nothing changes, I guess you don’t need a refill of wine—pass that jug to me, wise guy!” Zeno is grinning with wine-stained lips and doing a little shuffle dance off to the side.

Thunder cracks in a cloudless night sky. The olive trees slump. The waves seem to weep against the shoreline. The old Gods are in retreat. Something is happening here in Elea that forms a wedge between us and our experience of ourselves, between us and the relational nature of reality.

A rip in the seam of our beingness. An ancient rift in consciousness. Alienation.

II. How rational and scientific thinking crushed experience

Now, it might seem like some egghead making an argument in a town square in an Ancient Greek colony would be a fairly insignificant event. It wasn’t. Debate and intellectual argument were all the rage at this point in history, and Parmenides was making a play for the longevity of his ideas. He was subversive in doing it. He presents On Nature as an epic poem in hexameter, the same format used for Homer’s Iliad and other mythic stories. But this was the invention of metaphysics, delivered as myth.

This argument changed the course of Western thought, which changed the entire world. It echoed up through Descartes (“I think, therefore I am”) and seeded the future of philosophy and science that we’re living in right now. This new world is concerned with the true nature of reality and the elevation of abstract truths over experience and tradition. Feyerabend explains the consequences of Parmenides’ ideas and the world they helped create in a lengthy but important passage:

The search for reality that accompanied the growth of Western civilization played an important role in the process of simplifying the world. It is usually presented as something positive, or an enterprise that leads to the discovery of new objects, features, relations. It is said that it widens our horizon and reveals the principles behind the most common phenomena. But this search has also had a strong negative component. It does not accept the phenomena as they are, it changes them, either in thought (abstraction) or by actively interfering with them (experiment). Both types of change involve simplifications. Abstractions remove the particulars that distinguish an object from another, together with some general properties such as color and smell. Experiments further remove or try to remove the links that tie every process to its surroundings—they create an artificial and somewhat impoverished environment and explore its peculiarities. In both cases, things are being taken away or “blocked off” from the totality that surrounds us. Interestingly enough, the remains are called “real,” which means they are regarded as more important than the totality itself. Moreover, this totality is now described as consisting of two parts: a hidden and partly distorted real world and a concealing and disturbing veil around it.

In psychology and therapy, a great example of an abstraction is one that my dear friend Tara Behr often points to: referring to someone as a “nervous system.” This serves to simplify (person becomes nervous system) and introduces sameness (we’re all nervous systems). The map then becomes the territory: I often hear people in Boulder who’ve been in years of body-focused therapies talk about themselves as “my system.” A classic example of a psychology experiment is trapping a bird inside a chamber and then teaching him that pressing a lever results in getting food. You’ve isolated this being in an artificial environment, falsely assumed objectivity (you’re still in relation to the bird, albeit in an abusive and disassociated way), and then reported what you take to be an incremental truth about animal or even human behavior.

Two insights from Feyerabend’s quote stand out to me. One is that “real,” at least in part, has to do with what we value or prioritize. It’s easy to see an example of this in any magazine article about mental health. Here’s one from The New York Times a few weeks ago: It’s Not Just a Feeling: Data Shows Boys and Young Men Are Falling Behind. The story may mention people and their experience, but that’s “just a feeling.” When it comes to arriving at some kind of higher truth, the last word is always data from a scientific study, which is both abstract and experimental and—oddly, as Feyerabend points out—considered more true. We value certain truths more than others.

We are in a kind of trance of the truth. This is what we inherited from the legacy of Parmenides.

The other insight is that we made a trade-off on that day in Elea. It didn’t fully ripen until the scientific and technological revolutions of the past five hundred years. In exchange for the pursuit of a new kind of truth and knowledge, we sacrificed our experience and our relationship to the world. We became a separate observer, obsessive in our collecting, categorizing, tinkering, changing, and controlling. We know a red-winged Blackbird through her genus, species, plumage and molt patterns, genetics, how she responds to poisons that keep her from corn crops. Peering through our instrument of magnification, binoculars, we observe this winged one standing on a cattail in the marsh. Meanwhile, no amount of facts and truth satisfy our hearts’ longing for something we’re missing, in part because we have lost our capacity to be with the red-winged Blackbird, to experience each other in a relationship. We’ve convinced ourselves of our apartness.

Whether this trade-off was worth it is for each of us to decide.

Scientific thinking has predictive power that transforms the world and supports the kind technological production we value at this point in history. Does this mean it’s more true or more real? That’s a hard case to make. It seems ridiculous to say that scientific progress makes us a better or more successful culture than, say, the Ancient Greeks, the Minoan civilization, or indigenous peoples who once thrived in the present day U.S. By what measures? We can fly into space, edit the genome, and modestly lengthen lifespan; we also stare into screens all day, poison our food supply, and have completely desecrated (through medicalization and mechanization) the most sacred practice of all: giving birth to new humans. Scientific fields have given us great innovations and horrible blunders. We are brilliant and deranged.

And what happens if we draw Nick Bostrom’s “black ball” from the giant urn of possibilities? That’s the AI-oriented philosopher’s name for technological inventions, like nuclear weapons, that are existentially dangerous and can never be put back in the box. Or maybe we’ve drawn one and we don’t yet know it. In a famous essay on technology, Martin Heidegger says, quoting the Ancient Greeks: “That which is earlier with regard to its rise into dominance becomes manifest to us men only later. That which is primally early shows itself only ultimately to men.” We don’t know what’s really happening until after it’s already upon us. Perhaps science and technology, a few hundred years hence, will look like an epistemological addiction that got out of hand when we should have been minding the Gods, or at least minding

Our bodies. Our words. Our intuitions. Our experience. Our relationships.

III. The return home

Let’s pack up our little wool carry-ons and get ready to return from Elea. It’s morning now and you and I have had a good sleep on the ground. I’ve chartered a boat for us and lit a small fire on the beach for grilled sardines. The warmth of the sun rising in the west is reassuring. Our little philosophical vacation has come to an end. We two of us, wandering through time, seeing how peculiar and happenstance history seems to be.

Words. Some people think they don’t have the power to heal, yet here in Elea they were once so powerful that they changed the way we humans stood in relation (that is, out of relation) to the world. This materially transformed the world.

Like my mentor Bruce said: Words are psychoactive.

I think beneath the tendency to disparage our words is a longing to cultivate them again in a primal way. To each learn the poetics of our souls. To let them have a sacred life again. In therapy, to use words to help each other become more alive, real, and fully here. Words were once of the Earth. We talk about the “roots” of words because words have a deep-seated source in experience, in our relationship with the inner and outer worlds—originally with the planet we inhabit and with each other. The author Robert Macfarlane writes in his book Landmarks about the intimate relationship between words and landscapes. Language originates in nature and how we relate to it shapes our world. Macfarlane reports that the Oxford Junior Dictionary has been replacing the names of animals and plants with technological terms in dictionaries for children.

Out are acorn, fern, heron, pasture, and willow. In are attachment, blog, bullet-point, celebrity, and committee. The reason given by the editor of the dictionary is that those words just aren’t that useful to children anymore. Carrying on in the spirit of Parmenides, we move away from the here and now into abstraction. “And what is lost along with this literacy is something precious: a kind of word magic, the power that certain terms possess to enchant our relations with nature and place,” Macfarlane writes.

What is true is what we value. What do you value?

For me, in my own life, as a coach and future therapist, I value the full reclamation of my humanness in relationship with others. This includes “the ecological restoration of our interior world,” as the writer and polymath Stephen Harrod Buhner puts it, and the ability to share that world with others through presence and language. Psychotherapy can be a place to do that if it’s carried out in the tradition of “attending to the soul,” but not if it's mired in abstraction and experimentation.

Love the way you took us into the ancient city center for a philosophy treat. Well researched too!